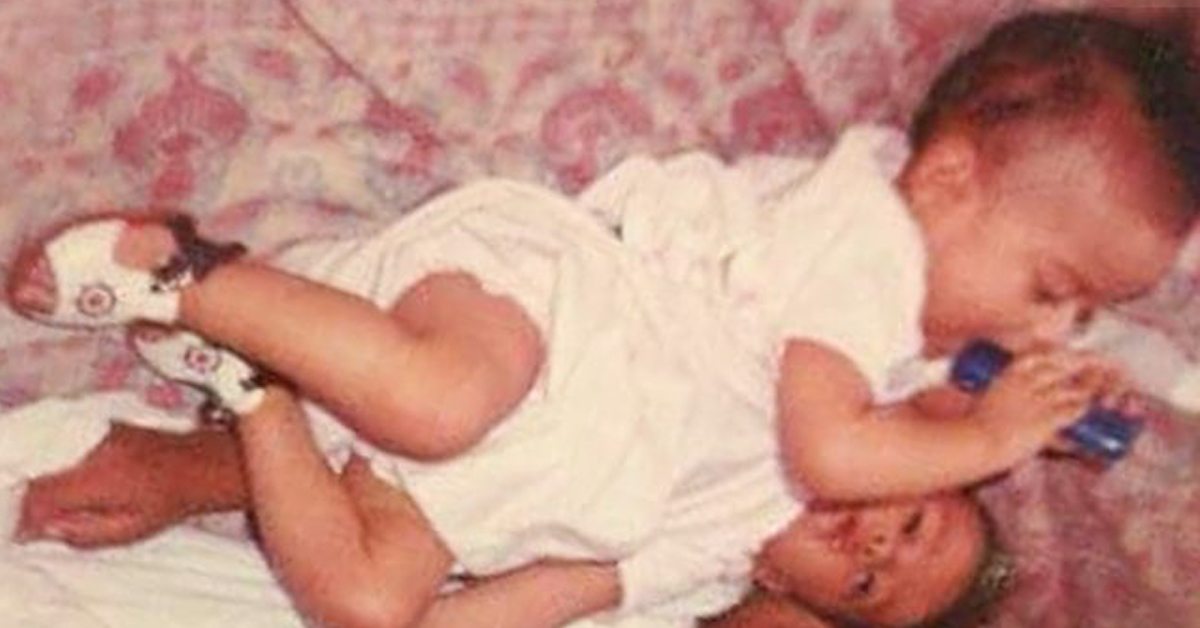

The girls are among the country’s very few sets of conjoined twins. They are attached along their chest walls down to their pelvis where their spines meet. They each have two arms, but only a single leg, with Carmen controlling the right and Lupita, the left. Bound together inextricably, with every movement demanding extraordinary coordination and cooperation, they wouldn’t have it any other way at this point.

“We’re so dependent on each other,” explains Lupita, who doubts they could “get used to not being dependent on each other.”

Most of the time, Carmen and Lupita are absorbed in teenage priorities like schoolwork and friends, but more daunting questions lie along the road ahead.

In a world that instantly sees them as different, Carmen and Lupita face imposing challenges that aren’t nearly so visible.

Serious medical issues could one day mean delicate surgery or an oxygen tank for Lupita, whose curved spine is cramping her lungs. The girls also face fears that their family, who came from Mexico seeking medical attention for them when they were babies, might be forced to leave the U.S. if President Donald Trump does away with the work permit program that has allowed them to stay.

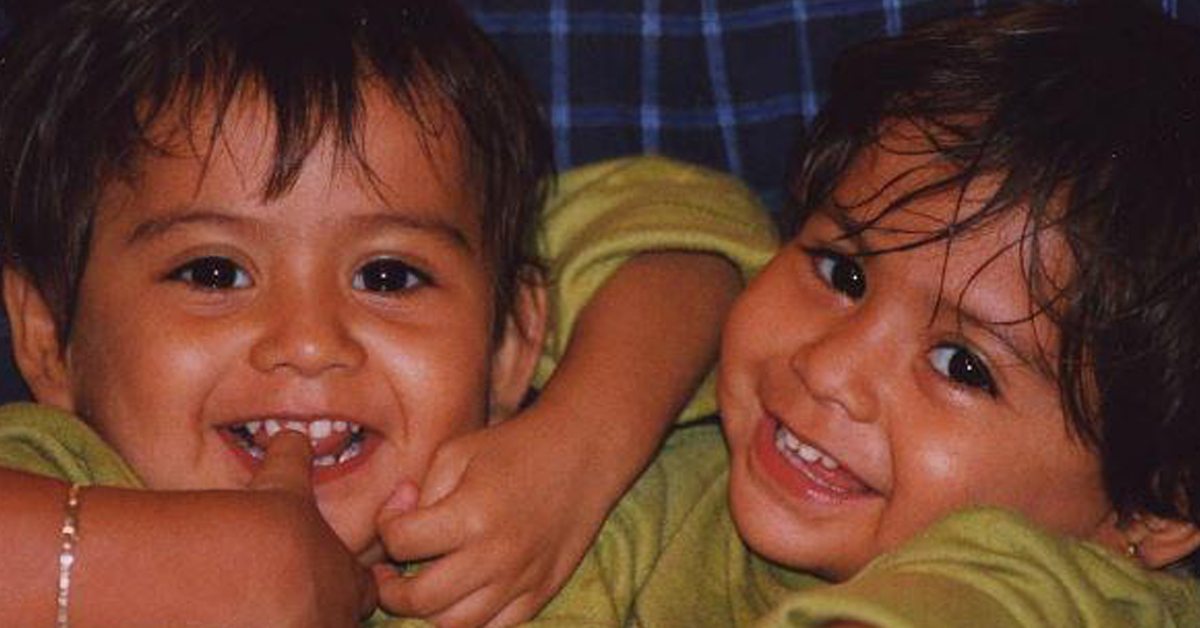

The girls each have a heart, a set of arms, a set of lungs and a stomach, but they share some ribs, a liver, their circulatory system, and their digestive and reproductive systems. Years ago, they spent long hours in physical therapy, learning how to get up off their backs and sit and use their legs together. At the age of 4, they took their first steps.

When they were tiny, doctors considered separating them, but concluded it couldn’t be done safely.

They have learned to balance and coordinate every move, bracing themselves at times to offset the strain of supporting two upper bodies on one set of hips and one pair of legs.

Theirs is a life lived in tandem that is so practiced, the girls say it’s instinct now. When they are in a cafeteria, one will reach for lunch and it’s almost always just what the other wants too; in the evening when they choose an outfit for school the next day, they seldom differ on what to wear.

“We kind of, like, have to agree,” Carmen says. “It’s obvious.” Their mother, Norma Solis, buys two of the same tops, dresses and coats, and then has a friend sew them together, tailoring them to fit.

Often, they finish each others’ sentences.

Describing how they handle the insensitive comments of strangers, Carmen said, “So if somebody asks us, like, if we’re twins, either I or mostly Lupita would just respond ….”

“No, we’re really close cousins,” Lupita says.

But the twins also have markedly distinct personalities. Carmen is a strong student, witty, sharp-tongued and ambitious. Lupita is quieter, has trouble with reading comprehension and takes modified versions of tests, but like her sister can be quick with a pointed, often humorous remark.

“A lot of people don’t notice, like, because when they first meet us, we kind of have the same reactions …,” said Carmen. “But our friends, once they get to know us, our friends literally tell us, ‘You guys are so completely different,’ and I’m like, ‘Well, yeah. We’re two different people.'”

If she needs time alone, Lupita will go on their cellphone or computer; Carmen will stay up late scrolling through social media on the phone while her sister sleeps beside her.

Day to day, the twins’ dreams and concerns are like those of any teenager. They talk about midterms, school projects that need to be completed, the SATs, friends, getting their learner’s permit to drive, practicing the piano. They have a list of colleges they are interested in, including the State University of New York at Cobleskill and Unity College in Maine.

One day Carmen would like to get a car, a big Chevy Silverado, she says, or a Ford F-150 to drive around the state and visit friends.

“You may look different but you still try to be like everyone else,” she explains.

“Ag is our safe haven from school, basically,” Carmen says about the agricultural program at Nonnewaug. They hope to have a career as veterinarians or in some aspect of animal husbandry. “We learn a lot but we still get to get a lot of hands-on experience. We wouldn’t just look at a picture of a cow … We actually touch them.”

Both girls say they prefer animals to people in many ways.”They don’t talk,” Lupita explains. “They know what you’re feeling because they get [it] off of your vibes.”

Animals don’t ask questions or raise more issues than either sister wants to think about.

“It’s more therapeutic than actually talking it out with a counselor or things like that,” Carmen said of working with farm animals. “I guess because they don’t speak,” she said, or ask “how do you feel about that?”

If Carmen catches a cold, she recovers quickly, but if she passes it to Lupita it could land them in the hospital. When Lupita has trouble breathing, Carmen finds herself breathing harder to compensate.

Surgeons don’t have much experience operating on conjoined twins because there are so few of them. Their incidence is extremely rare with an estimated one in 200,000 live births of conjoined twins. Most conjoined twins are still born or die shortly after birth.

Conjoined twins are formed when a single fertilized egg starts to split into identical twins soon after conception but stops before the process is completed. The chance that the twins can be separated depends on when the egg stopped splitting. If early on, the babies may share many organs; if later they are likely to have fewer shared systems and separation would be easier.

“The worst-case scenario is that you die from the surgery and that’s a possibility,” he said. “Short of losing your life, you can lose neurologic function. If you lose neurologic function and one or both legs don’t work, you’ll know about it right away.”

The twins also know what it’s like to be gawked at or to be subjected to unkind remarks while out in public where people don’t know them.

Carmen has sassy responses ready for anyone who stares too hard or is rude. “I tell them we’re a science experiment that went terribly wrong,” she said. Or to the teenager who asked her: “Are you from another planet?” she answered, “Yes, New Milford.”

Others will simply say, “God Bless,” maybe out of pity, Carmen guesses.

And there are some who put dollars in their hands. “Apparently we’re a charity,” Carmen says dryly. They say they always try to give the money back but sometimes people won’t take it.

The twins realize that most of the misguided comments that people make — “Are y’all stuck together?” — are not born of malice.

“We can’t just despise the world,” Carmen said, “so I guess we just have to come to an understanding of that fact that people who are going to ask questions are either…” Carmen is interrupted by Lupita, who finishes her thought.

“They are either really ignorant, or they don’t understand.”

When asked if they would ever do the separation surgery, “There’s a lot more risk to it then it actually being beneficial so we…” Carmen begins.

“… decided not to,” Lupita says. “We’re just going to live out life and that’s it.”

Source : Daily Mail